Juneau Commission on Sustainability

Menu

Hydropower

Background

Southeast Alaska is blessed with abundant water and steep terrain, resulting in a huge hydro power resource. The total theoretical hydro potential of SE Alaska is probably in excess of 10,000MW of capacity, with only about 200MW of this potential already tapped. Much of this potential will not be developed due to environmental concerns, or is located in protected wilderness areas or national parks. However, hundreds of remaining hydro power sites (mostly small-scale) could be developed with minimal environmental impact. Most of the region’s existing and proposed hydroelectric sites are lake-tap developments, on relatively small drainage basins with heavy runoffs. These lakes, typically formed by glaciers which receded after the last ice age, are perched at higher elevations, with tunnels or penstocks leading to powerhouses at lower elevations. Lake-tap projects often do not require a dam, and thus tend to have relatively low environmental impacts.

Regional hydro power resource assessment studies in SE Alaska date back to the 1920s, with the first report being “Water Powers of Southeastern Alaska” (US Forest Service, 1924). In the 1940s, the comprehensive study Water Powers Southeast Alaska (Federal Power Commission and US Forest Service, 1947) evaluated over 200 potential hydro power sites in SE Alaska, and also discussed a regional transmission system to interconnect hydroelectric plants and communities. The last regional study specific to small-scale hydro resources were commissioned by the US Army Corps of Engineers (CH2M Hill, 1979). This 1979 study was a reconnaissance-level analysis of mostly small (less than 10MW) run-of-river sites near twenty small communities in SE Alaska. A more up-to-date region-wide small hydro resource assessment is needed.

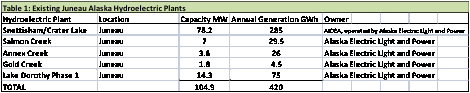

SE Alaska’s largest hydroelectric plant is the 78MW lake-tap Snettisham facility near Juneau. In addition, the region has sixteen existing hydroelectric plants in the small (1MW-50MW) category, six mini hydro plants (100kW-1MW), and at least ten micro hydro (less than 100kW) installations.

Source: Water Power Magazine. Brian Yanity 2009; http://www.waterpowermagazine.com/story.asp?storyCode=2053893

Juneau’s Hydropower and Grid System

Juneau’s electrical grid extends from the end of Thane Road at its southern boundary to end of North Douglas road to the Hecla Greens Creek Mine on its western boundary. High power transmission lines extend to Lena Cove where a smaller transmission line further extends to the Eagle Beach area on the northern boundary of the Juneau Grid system.

On December 5, 2012, the City and Borough Assembly passed Resolution 2632: A Resolution Expressing Assembly Support for the Extension of Electrical Power along the Veterans Memorial Highway. This extension would provide electrical transmission and service to the northern public and private lands of the City and Borough of Juneau.

Juneau Hydropower Plants existing, under development and planned supply

Juneau, Alaska was a pioneer in early hydropower development. This development was ushered by the Juneau Goldbelt mining operations which needed low and lower cost energy to extract gold from low grade ore bearing rock. The early hydropower plants of Juneau: Annex Creek and Salmon Creek Dam were developed to serve the mining industry. Today, Juneau receives most of its electrical generation from hydropower that is supplement by diesel. In 2012, the Coeur Alaska Kensington Mine installed its 7th diesel generator in order to keep up with its growing demand for energy. The Coeur Alaska Kensington Mine is 100% on diesel generation and the Hecla Greens Creek Mine switches to 100% diesel generation whenever water reservoir levels are too low for AEL&P to supply them with electricity.

Juneau has five operating hydroelectric facilities and two under development or planned stages to meet current and future demands for Juneau’s economy.

![]()

![]()

Sources- FERC preliminary permits, FERC licenses and Personal Communications—

Energy capability in Juneau depends on precipitation. In a very dry year, energy capability is 357 gigawatt-hours per year (GWh); in an average year, energy capability is 420 GWh per year; in the wettest years, energy capability is 518 GWh per year. In 2010, total GWh consumed was 396; had there been additional energy produced, it could have been used by non-firm customers. (Personal communication, Scott Willis, May 2011 for CBJ Climate Action Plan).

Juneau Hydropower Electrical Supply and Demand

(From CBJ-Community Development Department-Planning Commission Document)

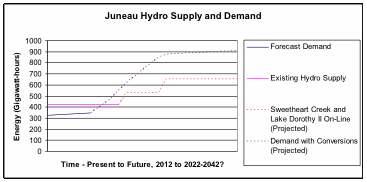

As the simple set of projections shown in the figure below, Juneau Hydro Supply and Demand, shows, conversions of heating and transportation energy sources from oil and gas to electric have the potential to raise the community’s demand for electricity beyond what is available. In this Figure, the Demand with Conversions (Projected) line shows what would happen if all existing and new heating and vehicles were converted to electric systems, using current technologies.

The cost of generating additional electricity with diesel would raise the cost of electricity so as to eliminate much of the financial justification for conversion;however, the increased cost of additional energy generated by diesel would be diluted with existing lower-rate hydropower, and could still yield economic ratepayer advantages for conversions. The take-away from this graph is that Juneau’s potential hydroelectric supply can easily be outstripped by Juneau’s demand for energy, and that conservation of existing supply and reduction of demand will be necessary to avoid reliance on expensive diesel-generated electricity in the future.

Figure 1: Juneau Hydro Supply and Demand (Source: CBJ Community Development)

Juneau’s hydropower resources are not limitless. In years with low rainfall, hydropower production must be supplemented with standby diesel generation. Permitting and Licensing new hydropower facilities, which is regulated the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is a time consuming process. Permitting and licensing on a national average can take three to five years with one to two years for construction. Therefore, the lead times required to place additional hydropower facilities on line take long planning horizons.

Juneau has a hydropower project currently under development at the Sweetheart Lake Hydroelectric Project and a planned future hydropower project at Lake Dorothy Phase II.

What would cause Juneau to need more hydropower?

The Regulatory Commission of Alaska tariff provisions require a regulated utility to serve all customers within its service district. Most of the City and Borough of Juneau road system is in the service area of AEL&P. However there is no utility service north of Eagle Beach in the northern section of the CBJ.

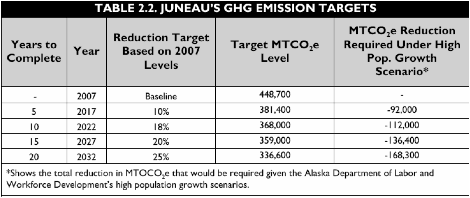

Juneau is in hydropower balance with firm rate customers. That means that those AEL&P customers in rate classes that are firm and not “interruptible” have current hydropower generation to meet their demand. Interruptible rate customers such as Hecla Greens Creek Mine, which is the largest single interruptible customer of AEL&P, is historically taken off AEL&P generated power whenever water reservoirs are too low to satisfy firm rate payer current and expected demand. Other interruptible customers include the Princess Cruise Ship dock and the Federal Building heating system. In addition, the Coeur Alaska Kensington Mine in the City and Borough of Juneau is not in the AEL&P service area and is connected to the Juneau electrical grid. The Coeur Alaska Kensington Mine produces 100% of its power with diesel generation and through no fault of their own, is the largest emitter of carbon emissions in the CBJ. Interestingly, the Coeur Alaska Kensington Mine produces and uses more electrical power than the City of Skagway and the City of Haines combined[1]. A Coeur Alaska Kensington Mine interconnection to a hydropower source would materially help meet and perhaps exceed the CBJ Climate Action Plan goals of community reduction in green house gas emissions of a 10% reduction by 2017.

[1] Source- Alaska Power & Telephone, the electrical utility for Skagway and Haines

Table 2. Juneau’s approved GHG Emission targets (Source 2011 CBJ Climate Action Plan)

Economically, limited or a lack of adequate hydropower over time could negatively impact Juneau’s economic growth and could lead to more diesel generation or other more carbon emitting fuel supply usage in the Capital city when electrical demand outstrips hydropower electrical supply.

Juneau’s total electrical sales (firm and interruptible customers) grew 10.83% compared from November 2011 to November 2012. AEL&P sold 329,250,834 kWh in 2011 and sold 364,906,469 kWh in 2012 through November of each year.[1] These sales numbers do not include December sales of either year. Hydropower projects are reliant on precipitation and rain fall. Lower water years means that hydropower projects produce less power than in higher water years.

Industrial and commercial growth is not the only electrical energy demand looming for Juneau. In addition to economic growth that could develop by means of new subdivisions, new commercial ventures, and new mining activity, there is also economic fuel substitution that occurs when people switch from high cost fuel sources to lower cost fuel sources. Based solely on the cost of competitive fuel sources (aside from the impact on GHG), oil to electric conversions growth is the other primary reason that Juneau will need more hydropower in the near and long term future. The recent draft Southeast Integrated Resource Plan (SEIRP) identifies the “Oil to Electric” conversion phenomenon as a threat to hydropower dependent communities.

“In communities where hydroelectric power is available, rapid conversion from heating oil to electricity for space heating has been common in recent years due to the lower cost of hydroelectric electricity for home heating and other uses. While a benefit to users who convert to electricity, this has had the effect of reducing the availability of excess hydroelectric generation and increasing the reliance on diesel generation for communities having limited hydroelectric capacity”[2].

The price of oil drives the amount of space heating load converted from oil to electric.[3]

[1] AEL&P Tariff Advice No. 413-1 Regulatory Commission of Alaska December 12, 2012

[2] Final Draft SEIRP page 3-25

[3] Final Draft SEIRP page 15-2

Figure 2. Achilles heel of the current hydro system (Source AELP 11-12 presentation slide)

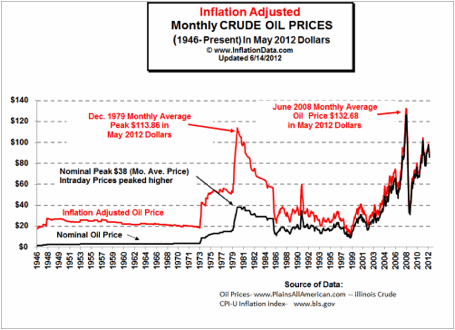

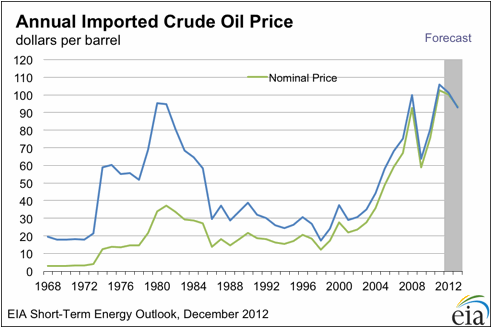

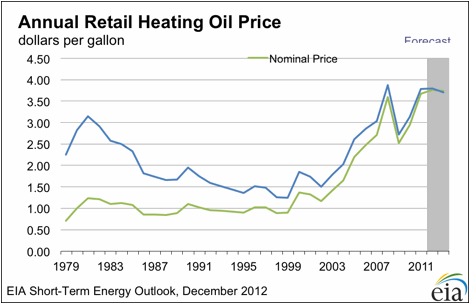

There are many factors that impact the price of home heating oil that impact why someone would substitute home heating oil with electrical heat. Many of these factors are international in nature and are therefore directly related to the world supply and availability of oil at any given time. However, in the past, diesel fuel used to be an economical form of electrical generation through diesel generation that was on par with hydropower. This is no longer the case. The charts below depict how oil prices have risen over time and demonstrate the correlation between oil imports, diesel costs and local Juneau home heating fuel costs.

Figure 3. Inflation adjusted monthly crude oil prices. www.inflationdata.com

Figure 4. Nominal and actual price for imported crude oil chart.http://www.eia.gov

At 2012 diesel fuel prices, the cost per kWh of diesel generated electricity is over .30 a kilowatt hour. In economic terms, continued increases in home heating fuel prices will have home and business owners migrate to lower cost heat sources such as electricity generated by lower cost hydropower. Over time, these conversions, combined with economic growth, will utilize the current hydropower capacity of Juneau’s existing hydroelectric facilities. At first, capacity and generation used by “interruptible” customers such as Hecla Greens Creek Mine and Princess Cruise lines will be decreased to ensure that there is enough electricity to meet growing electrical heating demand for firm ratepayers. It is not a question of if, but a question of when Juneau will eventually run out of currently developed hydropower resources. When this happens is predicated on economic development, the price of oil and the price of substitute fuel sources. Electricity is now, and with higher oil prices will become, a favored home heating fuel substitute to diesel.

Figure 5. Annual Retail Heating Oil Price Chart. http://www.eia.gov

Higher home heating fuel prices is a double edged sword with two negative consequences. As home heating fuel prices increase, a tipping point is created somewhere on the price continuum. An economic tipping point is defined asthe crisis stage in a process, when a significant change takes place. In the case of Juneau’s tipping point from oil to electric heat conversions, it might be a quick rise in the price of home heating fuel to $7.00 or $8.00 a gallon (or perhaps less) whereby home heating fuel oil is decreased and a large spike of demand occurs for electricity as smart households mitigate their home heating costs. Tipping points naturally occur in all markets and economies where substitution begins slowly and then a massive shift occurs over a relatively short period of time. For example, American adoption of cellular phones went from nonexistent to large scale use when the cost of ownership and cellular local and long distance rates dropped below what was typically charged for land line telephones.

If Juneau does not preplan and maintain a growing supply of hydropower and a tipping point occurs, it could have an expensive impact on Juneau’s economy and household disposable incomes. Interruptible ratepayers will be impacted first by a loss of excess hydropower capacity. After the interruptible power capacity is consumed by the migration from oil to electric conversions, additional generation will need to be supplemented with diesel generation at high fuel costs. While the addition of diesel generated costs will be diluted into the hydropower mix and cost of supply, diesel generation will add small but incremental costs to Juneau ratepayers by a fuel cost adjustment.

Juneau’s Climate Action Plan addressed this issue in the executive summary. The community’s challenge is to use its clean energy wisely in order to stretch existing hydroelectric capacity as far as possible, limiting the need to use back-up diesel generators. The Juneau Climate Action Plan has the following strategy and actions:

Strategy RE3-A.

Develop an energy plan for Juneau to ensure sufficient renewable energy resources for future growth that reduce/eliminate GHG emissions.

Under this strategy, the CBJ Climate Action Plan calls for the following short term strategy:

Develop an Energy Plan for the community to identify and evaluate the economics of renewable energy sources (including hydroelectric, biomass, solar, tidal, and wind) that will be able to meet the community’s needs in the future. The Energy Plan will need to be flexible enough to respond to changing conditions and will need to examine the full range of renewable energy potential and relative costs

Consider the feasibility of other potential hydroelectric sources to meet future needs such as Phase 2 Lake Dorothy and Sweetheart Lake.

Implement the recommendations of the Energy Plan to identify and develop local renewable energy sources.

Figure 6. Utility Planning Conundrum (Source AELP 2010 presentation Rural Energy Conference slide)

- [1] Source- Alaska Power & Telephone, the electrical utility for Skagway and Haines

- [2] AEL&P Tariff Advice No. 413-1 Regulatory Commission of Alaska December 12, 2012

- [3] Final Draft SEIRP page 3-25

- [4] Final Draft SEIRP page 15-2

Juneau Hydropower Conservation: past, present and future

One way to preserve Juneau’s hydropower capacity is simply to use less electricity through conservation measures and more efficient uses of electricity. On April 16, 2008 Juneau experienced a one in a hundred year avalanche that cut off Snettisham generated power from the Juneau electrical grid system. Aseries of avalanches damaged and destroyed the transmission towers along a mile-and-a-half stretch of the line that delivers hydropower to Juneau. As a result, Alaska Electric Light & Power had to supply all of its power from diesel generators, despite record-high prices at the time for diesel fuel. Diesel fuel consumption rapidly shot above 80,000 gallons per day, but once residents found out that electricity rates would increase from about 11 cents per kilowatt-hour to 52.5 cents per kilowatt-hour, the city and its residents rapidly pursued ways to save energy. As a result, Juneau’s peak power usage dropped from about 50 megawatts before the avalanches to below 30 megawatts by late May. Total electricity usage dropped from about 1,000 megawatt-hours per day before the crisis to roughly 600 megawatt-hours per day in late May, a 40% drop. For the last week in May 2008, the city’s diesel fuel use averaged only about 35,000 gallons of diesel fuel per day.[1]

A subsequent Snettisham avalanche in January 2009 led again to additional temporary conservation measures.[2]

Juneau has other examples of conservationism and efficient use of energy. The Juneau School District (JSD) has been a national leader in energy conservation. The Juneau School District incurred a $2,063,000 savings (through November 2011 equal to 28.28 percent of what energy costs would have been without the help of an innovative energy conservation program the district started in 2007.[3]

By implementing best practices for energy use throughout the JSD school system, energy savings are created, enhancing the learning environment and retaining dollars for education. The JSD system tracks energy consumption — including electricity, water, sewer, and fuel oil — using energy accounting software from EnergyCAP, Inc. The system compares current energy use to a baseline period and calculates the amount of energy that would have been used had conservation and management practices not been implemented. By tracking consumption and analyzing energy use, JSD staff can quickly identify and help correct areas that need immediate attention.

Four Juneau Schools Earn EPA’s ENERGY STAR®- Juneau-Douglas High School, Floyd Dryden Middle School, Auke Bay Elementary School and Glacier Valley Elementary School were each recognized by the Juneau Board of Education in 2010 for their success in saving energy. All four schools earned the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) prestigious ENERGY STAR, the national symbol for protecting the environment through superior energy efficiency. EPA’s ENERGY STAR energy performance scale helps organizations assess how efficiently their buildings use energy relative to similar buildings nationwide. A building that scores a 75 or higher on EPA’s 1-100 scale is eligible for the ENERGY STAR. All four Juneau schools achieved scores in the 90s.

Alaska Electric Light & Power has recently hired Alec Mesdag as an Energy Services Specialist to help and assist Juneau businesses and residences increase their energy efficiencies and implement conservation measures. For more information on energy conservation ideas, please visit the energy and conservation page of AEL&P’s website:

Hydropower cost inflation and volatility

Hydropower cost inflation and volatility as compared to other fuel sources is an important consideration in deciding whether to make capital investments to switch from one fuel source to another for Juneau home or business heating needs. Inflation and volatility comparison between fuel sources allows a decision-maker to better understand how much and how fast a particular fuel source has increased in the past to speculate the risk of how fast and how much a fuel source could increase in the future. Understanding the risk associated with fuel inflation and volatility is important in making expensive long term investments in boiler and heating systems which could have an operating life of two or three decades.

Some fuel source costs have recently increased significantly. Since June 2009, home heating #1 diesel fuel in Juneau has risen from $2.99 to $4.06 a gallon. This $1.07 increase over three years represents a 36% cost inflation or 12% per year. The table below represents the cost and volatility of home heating fuel in Juneau for the last three year period of 2009 to 2012.

Juneau Fuel Costs 2009 to 2012

Table 3 Juneau Diesel #1 Fuel Costs for 3 years

It is difficult to predict where an economic tipping point in the Juneau market exists from current heating fuel sources to a substitution of other energy sources. However, economic substitution will occur based on fuel comparison prices and the barrier cost (initial investment) to convert or add new fuel sources. A barrier cost being defined as the initial capital cost plus installation to supplement or switch from one heating system to another. Volatility of the cost from one fuel source to another fuel source impacts the investment risk and the decision to spend money to switch from one fuel source to another. However, it is relatively low cost to supplement a current oil based heating system with plug-in heaters (resistance heat) which are virtually 100% efficient. At times (depending on fuel price and oil burner efficiency), it is more cost efficient to use plug-in heating systems which have a low barrier cost.

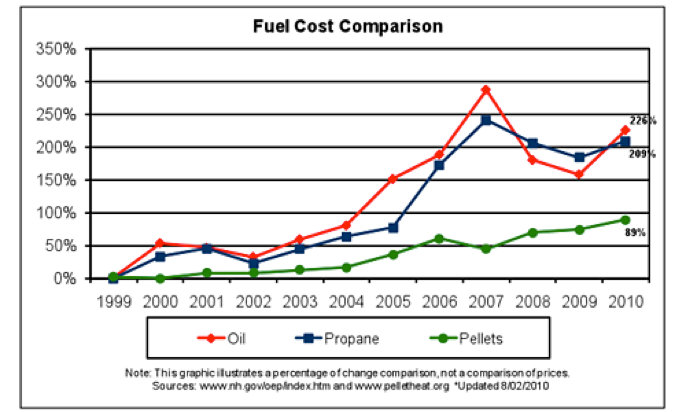

The Juneau Commission on Sustainability Website offers a Juneau Fuel Cost Comparison Chart for Juneau households and businesses to determine their heating costs and options based on fuel costs and efficiencies of heating systems. (To understand and compare how home heating fuel, propane and pellet fuel cost percentages have increased over the last decade, please see the Figure below. Juneau based electricity costs for Juneau has risen 27% in the last 11 years representing an annual inflation growth cost of 2.45% a year. Juneau’s electrical cost inflation and volatility compare favorably to local Juneau oil cost inflation average of 12% per year for the past three years and pellet fuel national cost inflation that has averaged 8% per year over the past 10 years.

Fuel Cost Inflation Percentage Comparison 1999-2010

Figure 7. Fuel Cost Inflation Percentage change comparison 1999 to 2010

- Fuel Oil Cost Growth 1999 to 2010 = 226%

- Propane Fuel Cost Growth 1999 to 2010 = 209%

- Pellet Fuel Cost Growth 1999 to 2010 = 89%

- Juneau Electricity Rate Growth 1999 to 2011 = 27%

Past demand growth, volatility and oil cost inflation are not a prediction of future increases. However past trends offer a reasonable scenario of what can be expected in the future.

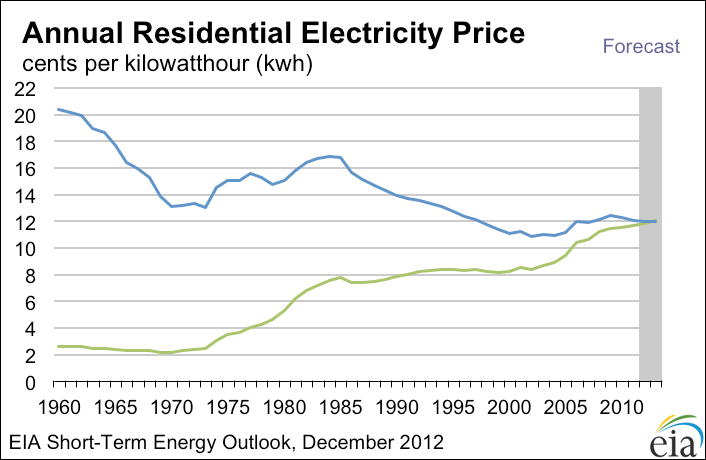

Figure 8 Annual Residential Electricity Price Chart. http://www.eia.gov

Based on the national annual residential electricity price, Juneau’s electrical price is near the national average. Juneau’s electrical cost inflation compares favorably to the national average cost of power.